As an unpaid law clerk, young Franklin Delano Roosevelt was already telling his fellow lawyers that he had no intention of making a career as an attorney. Instead, he intended to follow in the footsteps of his Uncle Theodore, and he had already mapped out his own path to the White House.

From the outside, FDR’s political ascendancy did look easy. The scion of a wealthy family, he appeared destined to become president—and his youth and vigor were a big part of his appeal. Early in his career, the New York Times described him thusly: “Tall, with a well set up figure, he is physically fit to command. With his handsome face and his form of supple strength he could make a small fortune on the stage and set the matinee girl’s heart throbbing.” Even when it looked like polio might put an abrupt end to his dream, his eventual recovery just made him seem heroic—born to privilege, the illness gave him a chance to prove his mettle. And as we all know now, he did win the presidency and would go on to serve four terms.

It’s an exceptional story. And, in the words of Steven Lomazow, “It’s complete bullshit.”

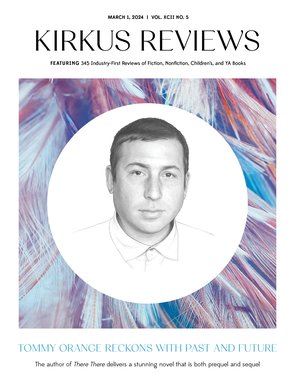

In FDR’s Deadly Secret (2010), co-authored with Eric Fettman, Lomazow uses his expertise as a doctor to review Roosevelt’s medical history and make the case that even though we know that Roosevelt was paralyzed for much of his presidency, his battles with serious illness—and the concerted efforts to hide them from the public—began much earlier than is generally supposed. In his latest book, Lomazow draws on newly available archival materials to offer a fuller picture of the president who led the United States during the Great Depression and the Second World War. Kirkus Reviews calls FDR Unmasked (2023) “an extensively researched and persuasive medical biography.”

“I mean, pardon my French, [but] I know this son of a bitch better than anybody alive. There’s nobody [else] who understands FDR like I do.” As Lomazow sits in the New Jersey office where he practices neurology, his passion for his subject comes through loud and clear. Roosevelt, the author says, is “the most influential personality of the 20th century.” The campaign of secrecy around FDR’s health is important because FDR was important. His efforts—and the efforts of everyone around him—to maintain the illusion of a man at the peak of his power changed history.

The coverup began, Lomazow says, in 1912, when Roosevelt contracted a terrible case of typhoid fever just as he was about to start campaigning for the New York Senate. Roosevelt was so weakened that “he literally couldn’t hold a pen.” His advisor Louis Howe—who would be an essential figure in all the coverups to come—wrote the candidate’s correspondence while spreading the lie that Roosevelt’s illness was mild and that he would be fully recovered in a couple of weeks. Howe would play a similar role when FDR contracted polio, laying the groundwork for a mythology that would endure throughout Roosevelt’s life and into the present day:

“I’m not going to mention the word ‘paralysis’ unless I have to,” Louis Howe told Eleanor. “If it’s printed, we’re sunk. His career is kaput, it’s finished.”

Thus began a twenty-four-year cover-up of the degree of Franklin’s paralysis and disability. Howe slipped some details to the Augusta, Maine, Daily Kennebec Journal. That newspaper’s August 27, 1921, headline announced, “Franklin Roosevelt Improving After Threat of Pneumonia.” He “had been seriously ill at his summer home at Campobello, but is now improving,” the article stated…. This became the mantra for describing Franklin’s condition—temporary and improving.

By examining medical records as well as letters, diaries, and other sources with a physician’s eye, Lomazow concludes that FDR endured severe gastrointestinal bleeding, two incurable cases of cancer, severe heart disease, epilepsy, and other maladies before he succumbed to a stroke in 1945. By the end of his life, FDR’s presidency was being held together by a conspiracy of silence that included everyone around him and the American press.

One of the reasons Lomazow felt compelled to write a second book on this subject was a cache of material unearthed at the FDR Library in 2016. In a file that was labeled as information about a “vacation cruise” the president took with his good friend Vincent Astor in 1934, Lomazow found ample evidence that FDR had, indeed, been treated for cancer—including a telegram sent to Roosevelt by a radiologist. Documents he found in this file led Lomazow to Dr. W. Leslie Heiter. “Nobody knows about this guy,” Lomazow says.

Pursuing this lead connected Lomazow to Bill Heiter, who has, as it happens, preserved his father’s papers. Dr. Heiter’s letters make it clear that he was, indeed, on a cruise that was supposed to be about rest and relaxation. “This guy trained at Sloan Kettering. And he’s on Astor’s boat at the same time as the president? That’s no accident.” The role that Astor—“the richest man on earth”—played in FDR’s political career is, in Lomazow’s opinion, underappreciated. It’s also emblematic of how much Roosevelt relied on his connections with incredibly wealthy and hugely influential people to protect him from public scrutiny.

Lomazow clearly relishes the role of medical detective, and anyone who’s read his work can tell that he’s a born storyteller. But conversation inevitably circles back to the question: Why spend 15 years on this story? When asked precisely this question—again—Lomazow expands on his initial answer. “So, did covering up his cancer change the New Deal? Probably not. But he got into World War II not just to win the war, but also to win the peace. He wanted to be the greatest president ever. This meant emerging victorious from WWII and building something better than Woodrow Wilson’s League of Nations.”

FDR wanted the United Nations to be part of his legacy. “That’s why he was willing to die from making the trip to Yalta. This is why he gave Joe Stalin anything he wanted,” Lomazow says. “For example…Stalin wanted control of Manchuria and the railroad. He wanted a couple of islands. No problem. Those were, as it happens, the exact things the Russians had given to the Japanese in 1905, because they had lost the Russo-Japanese war in 1905. What was the treaty that ended the Russo-Japanese War? The Treaty of Portsmouth. And who got a Nobel Peace Prize for that treaty? Theodore Roosevelt—FDR’s idol. To be the greatest president ever—which is exactly what FDR wanted to be—he has to be better than TR. This gets a little psychological, but I imagine FDR saying to himself, I’m going to kick little Uncle Teddy in the ass. I’m going to give Russia back everything that he took from [China] and gave to the Japanese. And of course, in exchange for all of this, the Russians were supposed to declare war on Japan. Yalta was in March. When do the Russians declare war on Japan? Not until August…after Hiroshima. And FDR didn’t live to see it. So how would Yalta have gone differently if FDR had been healthy enough to really deal with Stalin?” From here, Lomazow spins out an alternative history of the second half of the 20th century that—significantly—does not include a war in Vietnam.

Over the course of our conversation, Lomazow refers to FDR as “narcissistic” and a “snob,” but these quirks of personality do nothing to diminish his respect for the man. “Why was FDR a great president? Because in 1932, he could have gone the way of Mussolini. He could have declared martial law and closed the banks. He could have done anything. What did he actually do? The New Deal.

“And, look, this is a rich guy. When people heard him say, ‘We have nothing to fear but fear itself,’ they might have thought, Why should I listen to this socialite? What does he know about fear? But he did know fear, and he knew pain. His whole life was an act, but he was a smart guy, and a small-d Democrat, and he believed in the Constitution of the United States. That’s why he was a great president.”

Jessica Jernigan lives and works on Anishinaabe land in Central Michigan.