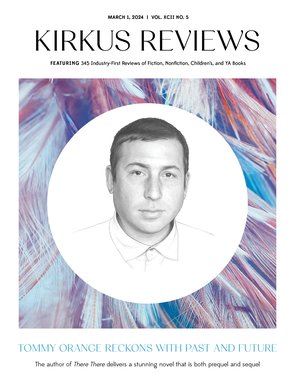

You realize you have stories to tell when you take a stab at writing your memoir and your first draft runs upward of 900 pages…and only takes you to age 40. So it went for retired anesthesiologist Otto Stallworth Jr. whose memoir, Are You a N****r or a Doctor? concludes with the invitation to “stay tuned for Part II.” (Editors helped trim the page count!)

Stallworth etches captivating sketches of growing up in the 1940s and ’50s in Birmingham, Alabama, which Martin Luther King Jr. called America’s most segregated city; leaving Alabama for the first time at age 16 to attend college (the first in his family to do so); and taking some surprising detours like, while still in medical practice, becoming the manager of the music group A Taste of Honey in their Grammy-winning “Boogie Oogie Oogie” prime.

The book’s provocative title is taken from one of its most memorable incidents. Stallworth, then 24, was in the third week of his internship at Case Western Reserve Hospital in Youngstown, Ohio. The year was 1970, and he was the only Black doctor among 25 interns and residents. One of his patients was an elderly white man, a retired chief of police of a small Ohio town, who had dementia. At one point, Stallworth must coax him out of the bathroom. The man, who had been staring down at his feet, finally regards Stallworth and asks the eponymous question. Stallworth’s response is a devastating, yet dignified, comeback.

Kirkus Reviews praises Stallworth’s memoir as “fascinating, moving…an extraordinary reembrace—as emotionally affecting as it is historically edifying.” It is, for example, one thing to read about Birmingham’s restricted water fountains and “White Only” signs in histories of the era. It is another to read Stallworth’s account of how, at age 7, he was compelled to drink from one:

Everything with White Only signs always looked better, and this White Only water fountain was no exception…I walked toward the fountain, licking my lips. Had to stop and wait until an older White Boy finished drinking. I pushed the lever. Harder to push than I expected. The White water gushed in my face. “It tastes like the Colored water, Mommy!” I screamed.

Stallworth fulfilled his childhood dream of becoming a doctor, but writing was a passion for him. “When I started [at] Howard University,” he says, “they gave you a test, and if you didn’t score well enough, you had to take remedial courses before you could take the actual course. I had to take English as a remedial course, and I resented that. So I always wanted to get better and worked extra hard in English-related courses.

“When I finished my residency, my cousin, a neurosurgeon, told me if you want to help prevent getting Alzheimer’s, you have to find something new that you can do. Taking up writing was something totally new to me. When I got to Los Angeles, I started taking extension courses at UCLA.”

Initially, he wrote a screenplay, a murder mystery (that he is currently adapting into a novel). But the idea came to write a memoir for his children and grandchildren. “I wanted them to know where I came from, and [to] compare how I grew up [with] their experiences,” he says.

Stallworth, who still lives in LA, grew up in a segregated southern neighborhood, where the families toiled in diverse professions. “My mother was a beautician, and my father worked in a steel mill,” he says. “A mother and daughter who lived next door were maids in white people’s homes; a teacher lived on the other side of our house; and a minister lived around the corner. Condoleezza Rice’s family lived a block and a half away.”

It was a classmate’s father, an obstetrician, who started Stallworth on his career path. “I was 6 years old,” Stallworth recalls. “One day, my parents couldn’t pick me up from school, and this man brought me to his office. I saw him working. It was the first time I had seen a colored doctor, as we called them then. Everyone in those days asked what you wanted to be when you grew up. I wanted to have an answer: doctor. I ended up believing it.”

There was one other thing that pushed Stallworth toward becoming a doctor. “I was a train fanatic,” he says with a laugh. “I had a train set. You pushed a button, and the train went around in a circle. I went to this man’s house, and he had a train set that took up two rooms. It had tunnels and waterfalls and bridges. I said, ‘I want a train set like this; I want to be a doctor.’”

Though his parents divorced when he was young, the people of his neighborhood served as positive role models for Stallworth at a time when opportunities for Blacks were diminished. “It was a nurturing environment where the family unit was strong,” he says. “No one told me I couldn’t be a doctor.”

Stallworth left Birmingham and Alabama in 1962, a year before the devastating church bombing that killed four young girls. Dr. King delivered a eulogy at the church Stallworth’s family attended. “I never heard him speak personally,” Stallworth says. “He started in Montgomery, which is only 100 miles away. We had attempted a bus boycott a couple of times. It was difficult to get people to cooperate, especially older people whose jobs depended on them not getting into trouble. When Dr. King came to Birmingham, people jumped on the bandwagon. Everyone in the community was supportive of him.”

As Jonathan Eig writes in his biography King: A Life, the civil rights icon received criticism for stating that the South did not have a monopoly on racism and that it was just as rife in the North. Stallworth experienced this firsthand when he visited Chicago, New York, and other major northern cities. “In the South,” he says, “you knew where they were coming from. It’s true that I did not see ‘White Only’ placards up north, but you had to develop antennas when you walked into an unfamiliar place. You could sense the hostility. The only difference between Chicago and Birmingham was there were no signs.”

Reflecting on his memoir, Stallworth said that a recurring theme throughout is being a fish out of water. “A high-rise [apartment building] in Birmingham when I was growing up might have been four floors,” he says. “When I went to New York as a teenager, I got off the bus and I was looking at buildings that had 51 floors. Everywhere up north I went after I left Alabama, I had trouble with my accent, the way I dressed. A lot of things were culturally different. I got a lot of flak from northern students.”

As for the incident that inspired the book’s title, Stallworth considers whether he would answer the man’s question differently today at the age of 78. Mostly, he reflects on the man with compassion. “That was probably the lingo of the community where he was brought up. I’ve heard the N-word spoken in a mean-spirited way, but it was almost like he was using the word in my presence as a synonym for ‘Black man.’ Because of his personal experience, I could only be one or the other.”

Donald Liebenson is a Chicago-based writer who is published in theWashington Post, Town & Country, and on vanityfair.com.